Examination techniques are universally recognized as a sensitive detector of disease. New imaging techniques enable a specific diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging is able to demonstrate joint erosions well before conventional X-Ray. However they do not replace the basic clinical examination. It is not uncommon for X-rays and blood tests to be reported as normal in the presence of disease. False positive tests are entirely possible. Interpretation of all investigations MUST be taken in the clinical context.

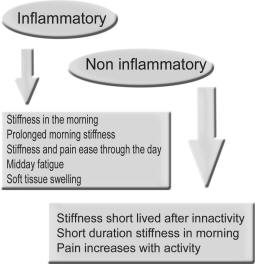

There are well over a hundred musculoskeletal related conditions. The starting point is to determine the difference between inflammatory and mechanical or degenerative process. Thereafter one can make an anatomical diagnosis of the precise articular or extraarticular structures involved and finally a pathological diagnosis.

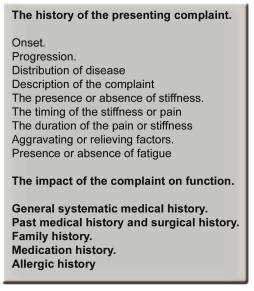

The History

A comprehensive history of the presenting complaint, the general medical and systematic history is obtained. Past history and family history should be obtained, as well as a list of medications and allergies.

Pain

Pain is the most common presenting complaint. Chronology of the pain and aggravating factors provide clues to origin. These include prior trauma for example, or even preceding infections causing reactive arthritis. Pain can be acute, for example, as in gout where the onset may be almost instantaneous or over hours, compared to pseudogout, which may occur over weeks and osteoarthritis, which can be gradual over years. Thirty percent of rheumatoid patients present with acute onset. Pain may wax and wane over days in cycles over months as in palindromic rheumatism.

Inflammatory pain is usually maximal in the morning and increases again at the end of the day. Mechanical pain is maximal with use, and activity. Night pain and rest pain may be frequently seen with bone diseases such as Pagets, but also is seen with malignancy. Neuralgic pain is usually diffuse in a dermatomal distribution worsened by specific activity, whereas referred pain is unaffected by local movement. Diffuse unrelenting pain described as constant and "all over" is often associated with Fibromyalgia. The description of pain may be very subjective. Joint pain is often described as aching, whilst nerve entrapment is frequently associated with shooting pain or like an electric shock

Stiffness

The duration of the stiffness, especially morning stiffness is proportional to the amount of inflammation. Degenerative process results in short duration morning or post rest stiffness. The stiffening of the joints is called "gelling". Inflammatory disease causes prolonged morning stiffness. In the case of Rheumatoid arthritis this usually exceeds an hour. In Polymyalgia, the stiffness is also typical in the morning and is usually proximal in the shoulder girdle, neck and thigh region.

Locking

Locking implies mechanical derangement of a joint or tendon. In the case of the flexor tendons of the hands, irregularity of the tendons within the tendon sheath may cause tendon entrapment and locking of the fingers. Joint locking occurs most classically in the knee, due to meniscus injury, and in the spine with disk or apophyseal joint disease.

Swelling

Subjective complaints of swelling are common and should be differentiated from the objective finding of swelling in joints or soft tissues on examination

Fatigue

Midday fatigue is a frequent complaint in inflammatory arthritis. Depression is also a frequent cause of fatigue. Exercise may well aggravate the fatigue of inflammation whilst making that of depression better. The presence of overwhelming fatigue is also extremely common with Fibromyalgia.

Cracking and clicking of joints

Cracking of the joints is known to be related to nitrogen bubbles "popping" into synovial fluid with negative pressure. This is usually a benign phenomenon and does not aggravate disease or progressive degeneration. Crepitus, however may be felt especially with mechanical change or cartilage irregularity.

Constiitutional symptoms

This includes fever sweats and loss of appetite and weight as seen in inflammatory arthritis. The practitioner should also be alert to other systemic diseases including underlying malignancy.

Systematic inquiry

Inquire about skin rashes, especially psoriasis, photosensitivity or raynauds. Mouth and genital ulcers, diarrhoeas or genitourinary infections may provide clues to spondyloarthropathy. Inquire about ophthalmologic problems such as red or dry eye as there is a close relationship between several rheumatic diseases and the eye, including Sjogrens or inflammatory eye involvement.

Impact on Daily life

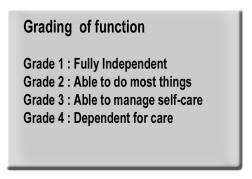

Inquire about the

effect on daily life and other psycho-social effects. An American

College of Rheumatology (ACR) functional

assessment classification is used to

assess function. Various scales are derived for different

illnesses including the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ),

for rheumatoid and the WOMAC score for Osteoarthritis. Occupational

history or repetitive strain activity may cause aggravating factors for

the complaint and should be documented.

The initial goal is to establish the anatomical source of pain. This requires differentiating between articular versus extraarticular source. Every joint should be assessed individually, and the soft tissue, contractile structures around the joint appropriately examined. The technique requires the classical "look - feel - move" approach of Apley and application of the concept of the capsular pattern of Cyriax.

Look

- Gait.

- Swelling.

- Redness in joints or tendons.

- Skin changes – Examine for psoriasis, raynauds phenomenon, ulceration of skin and rashes.

- Wasting of regional muscles

- Deformity or contracture.

Feel

Move

This technique is the most useful in localizing the pathology. There are three techniques of movement in the joint examination.

- Active movement. The patient utilizes his own muscles and contractile structures to move a particular joint through its range of movement. This tests the joint as well as the contractile structures.

- Passive movement: Here the patient is encouraged to relax and the examiner moves the joint through its accepted range of movement. By ensuring that the joint muscles are relaxed, this checks the actual joint capsule itself. The joint range of movement may be found to be reduced. This suggests age-indeterminate involvement of the joint. Reproduction of the pain on passive movement confirms the joint as source of the complaint. If the pain is not reproduced by movement within the capsular pattern, then the cause lies elsewhere.

- Resisted movement:

This isolates the cause to a particular

tendon or bursa. The joint is made to relax then force is applied by

the patient against resistance of the examiner. Reproduction of the

pain confirms the source to be the contractile soft tissue

structure.

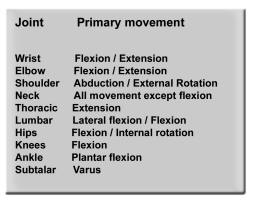

The capsular pattern is a range of movement that is affected by disease of the joint. In the case of active joint inflammation, passive movement in the capsular pattern will be tender. Should the complaint be reproduced in this manner, then the joint itself is the source of the pain.

Restriction in the capsular pattern suggests age indeterminate disease of that joint.

The joint examination - every joint is examned with the look feel move principals

Examination of the upper limb

The Hand

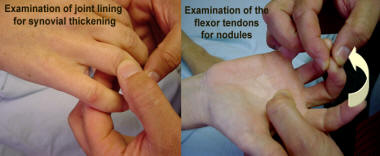

Each individual joint is examined, including DIP’s, PIP’s and the MCP’s as well as joints of the thumb. Swelling is recorded. The range of movement of the fingers is noted. The finger flexor tendons are then examined by feeling the tension in the pulps at the base of each finger. Tightness suggests tenosynovitis. (Saville sign) The flexors are then palpated for nodules in the palm whilst flexing and extending the fingers. These nodules may be a cause of locking.

The WristsThe wrists are palpated as a single bony unit for signs of swelling. Range of movement is tested. Flexion should be between 60-90 degrees and extension 60-90 degrees Restriction suggests an inflammatory arthritis. Hypermobility may be examined by extending the 5th finger to more than 90 degrees and moving the thumb against the volar aspect of the wrist. Tendonitis of the Abductor pollicis longus and Extensor pollicis brevis; De Quervain syndrome, which presents as thumb wrist and forearm pain, is checked by holding the thumb in a closed hand and stretching the tendon by adducting the wrist (Finkelstein’s test).

Check for sensory signs in the hand and for tap tenderness over the median nerve, (lateral to Palmaris longus tendon whilst extending the wrist - Tinel sign). Phalens test with flexion of the wrists produces aggravation of carpal tunnel symptoms.

The ElbowPalpate the radial and ulnar margins for synovial thickening. Palpate for nodules or tophi on the extensor surface of the elbows. Contracture or deformity is noted. Extension should be 0 degrees whilst hypermobility will allow more than 10 degrees of extension. Flexion of 145 degrees is normal. Movement at the elbow should be checked especially flexion and extension. Passive flexion and extension pain suggests elbow joint involvement.

Lateral epicondylitis (Tennis elbow), is tested by extending the wrist

against resistance, with the arm extended at the elbow, whilst palpating

the insertion of tendons at the lateral epicondyle. Pain at this point

is suggestive of extensor tendonitis.

Medial epicondylitis (Golfers elbow) is tested by resisted flexion of

the wrist with the arm extended, and palpating a tender point at the

medial epicondyle.

Bicipital tendonitis is found by flexing the supinated forearm against resistance, whilst palpating the tendon insertion at the elbow.

The Shoulder.Painful passive movement in the capsular pattern – abduction and external rotation with or without restriction at the joint suggests shoulder joint as a cause of the pain. Restriction of abduction and external rotation suggests age indeterminate involvement. The shoulder movement is glenohumeral up to 90 degrees and scapulothoracic from 90-150 degrees and glenohumeral from 150-180 degrees. The shoulder and scapula should be steadied when examining, to ensure movement tested is glenohumeral.

Painful resisted abduction and external rotation, tested by pressing

outward against resistance, is suggestive of rotator cuff disease. The

rotator cuff consists of the Teres Minor, Supraspinatus, Deltoid and

Infraspinatus muscles. The rotator cuff presents with pain at the

shoulder radiating down the outer aspect of the arm. Pain at the rotator

cuff with abduction weakness may suggest partial or full thickness tear

of the tendon.

Global painful restriction of the shoulder of unknown aetiology is

suggestive of adhesive capsulitis. The term ‘frozen shoulder’ applies to

such restriction with underlying shoulder or rotator cuff pathology.

Resisted internal rotation tests subscapularis tendonitis. Resisted

flexion of the supinated elbow with the shoulder in the neutral position

tests biceps tendonitis. This will be felt as tender in the bicipital

groove at the shoulder.

This presents with pain over the supraclavicular region radiating to the apex of the shoulder. Test by passive movement of the shoulder to extremes of movement – especially abduction, external rotation and adducting the arm fully in front of the chest.

Examination of the spine

Cervical Spine.

Neck disease with root symptoms may radiate to the shoulder, but active shoulder movement will not affect pain arising from the neck itself. A neurological assessment is required.

The neurocentral joints are most sensitive to extension, whilst the facet joints are most sensitive to lateral flexion and rotation. Rotation laterally should allow 60-90 degrees. Flexion should allow 60-90 degrees and lateral flexion 30-60 degrees.

Thoracic Spine.

The thoracic spine allows 45 – 75 degrees of rotation. Chest expansion should be greater than 4 cm.

Pain in the thoracic spine should always be properly assessed for cause. Feel for bony tenderness and pain on active and passive movement, including extension, lateral flexion and rotation.

Examination of the superficial muscles may reveal trigger points as seen in fibromyalgia. Intercostal muscle problems may produce pain with respiration, as will pain from the costovertebral and costochondral joints, with local tenderness.

Lumbar spine.

Check for lordosis or loss of lordosis and scoliosis.

Pelvic tilt may be noted and leg lengths should be measured from the anterior superior iliac spine to the medial malleolus at the ankle. A difference of one centimetre is acceptable.

Lumbar root symptoms will radiate to the appropriate dermatome and will have a sharp burning or electricity sensation with or without neurological signs. Forward flexion and lateral flexion may aggravate root symptoms, whilst extension will often aggravate symptoms of spinal stenosis. A positive straight leg-raising test suggests root entrapment.

Capsular joint problems, seen in inflammatory arthritis, produce symmetrical pain and restriction to all ranges of motion, flexion, lateral flexion, rotation and extension. The forward flexion is measured by the Shober test. A line is measured 10 cm above and 5 cm below the "dimples of venus" and then remeasured after the patient is flexed fully. The increase should be at least 5 cm.

Lateral flexion should be 30 degrees. Extension should be 30 degrees and rotation 45 degrees.

Hypermobility allows increased forward flexion, tested by ability to flex and place the palms flat against the ground.

The sacroiliac joint.

Palpate the joint itself, or apply lateral compression of the pelvis.

The hip joint.

As a general rule, whilst spinal pain may radiate below the knee, hip pain will not.

Observe the gait of the patient. Pelvic tilt may reflect leg length shortening or compensation for hip or spine disease. With an antalgic gait, weight bearing occurs with the patient leaning to the diseased side.

Weak abductors result in a Trendelenburg gait, with the pelvic tilting downward on the affected side.

Hip flexion is usually 120 degrees, Extension 10-20 degrees, Abduction 45 degrees, Adduction 20-30 degrees, Internal rotation 40 degrees and external rotation 45 degrees.

Examination for hip flexion contracture requires the patient to lie flat, and the lumbar lordosis neutralized by flexing the opposite hip. The involved leg is extended as far as possible and the angle to the surface of the examination couch recorded.

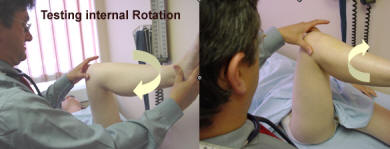

Restriction in internal rotation is a very sensitive method of assessing hip joint disease. The hip and knee are flexed to 90 degrees with the patient lying flat, and the hip is rotated by holding the knee and moving the foot outward from the midline. This movement constitutes the capsular pattern and will reproduce pain for active hip joint involvement with or without restriction of range of movement.

The testing of movement against resistance is used to detect soft tissue problems.

Trochanteric bursitis presents with lateral thigh pain aggravated by lying on the side. It is detected by laying the patient on the side and abducting the thigh against resistance. Palpation at the greater trochanter confirms tenderness. Ilio-psoas bursitis is detected as painful resisted flexion.

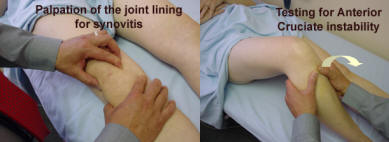

The knee.The knee is inspected for swelling, deformity and posteriorly for popliteal (Bakers) cyst. Regional muscle atrophy of quadriceps is common in derangement of the knee. Feel for heat or swelling in the joint. Swelling can be bony or soft with synovitis. Foreign bodies may be felt.

Knee extension should be 0 degrees, flexion 120-150 degrees. Hyperextension greater than 10 degrees is seen with hypermobility.

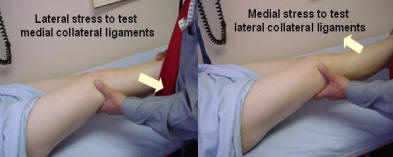

The stability of the knee is assessed looking at the cruciate ligaments, the menisci and the lateral ligaments. The lateral ligaments are tested by applying valgus and varus stresses to the extended leg.

The cruciates are tested by the ‘Drawer Test’. The knee is flexed to 90 degrees with the hip at 45 degrees. The leg is held around the calf and the tibia pulled forward. More than 6 mm of movement suggests anterior ligament tear. The tibia is pushed backwards and more than 6mm of displacement suggests posterior cruciate tear.

Meniscus injury causes locking and clicking with mobility. The medial and lateral margins of the joint may be tender and flexion of the knee to 90 degrees whilst rotating the lower leg internally produces pain.

Examination of the soft tissues include the supra and infrapatellar tendons which may be tender locally and aggravated by resisted knee extension. The anserine bursa is located medially below the joint margin and may produce local tenderness.

The Ankle and Subtalar joint.Inspect for swelling and deformity. Palpate for swelling and examine the range of movement. The ankle movement allows 20 degrees of dorsi-flexion and 45 degrees plantar-flexion. The subtalar allows 30 degrees inversion and 20 degrees eversion. Passive movement will test for regional inflammation of the ankle by flexing and extending the ankle and inverting and everting the subtalar joint.

The peroneal tendons are found laterally and extend the ankle and pronate the foot. The medial tendons plantarflex the ankle and supinate the foot. Resisted movement will test the respective tendons.

Stability of the medial and lateral ligaments is tested and derangement of the joint with weight bearing is essential.

The Achilles tendon is inspected and palpated locally for tenderness.

Tarsus.

This is examined as a single unit with inspection for deformity and swelling as well as palpation for synovial or bony thickening, and movement for tenderness and restriction. Movement includes dorsiflexion, plantar-flexion, adduction, abduction, medial rotation and lateral rotation. The adduction and medial rotation constitutes the capsular pattern.

The plantar fascia is palpated at the calcaneus for insertion tenderness.

Toes.

Inspect for deformity, nodules or bony or soft tissue swelling. The capsular pattern consists of flexion and extension. Extension is the most sensitive. The metatarsals are examined, successively for callous, synovial thickening or tenderness. The metatarsals can be tested by squeezing them together to elicit pain. The great toe can usually flex 30 degrees and extend 90 degrees. Bonny swelling or bunions are noted.

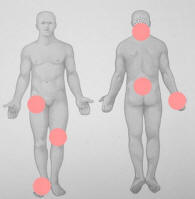

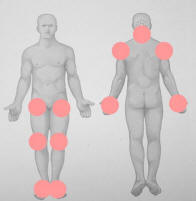

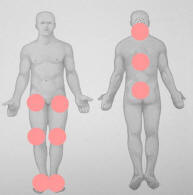

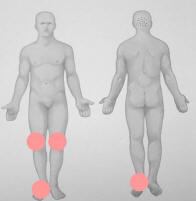

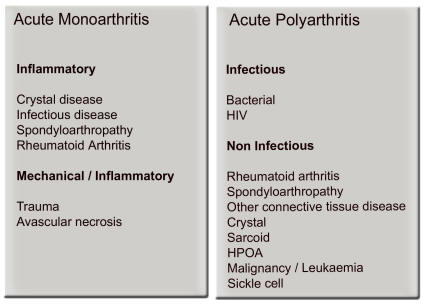

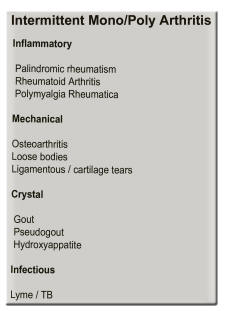

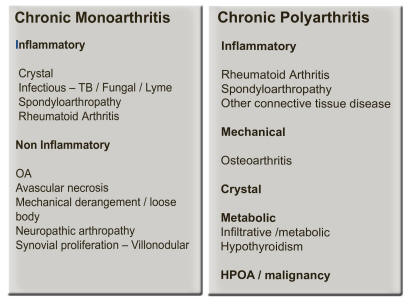

Conclusion.The history and examination provide the main information to making a diagnosis. The distribution of the problem, combined with the information regarding presence or absence of inflammation, are then correlated and interpreted. These together with pattern of presentation are vital clues to the definitive diagnosis (Fig 5,6,7).

The severity of the problem is then quantified and the effect on function and daily life are the main issues that determine aggression of therapy. ‘Pain killers’ do not alter prognosis of inflammatory disease.

The main focus of therapy should be early use of disease-modification.

With the presence of increasingly familiar imaging techniques, early changes are visible on MRI that are otherwise seen as normal on X-RAY.

The normal laboratory tests and X-rays do not replace a good examination.

The fundamentals of examination remain the cornerstone of Rheumatology.

References

1. Kelley’s textbook of

Rheumatology 6th Edition. WB Saunders

Company New York.

2. Rheumatology Klippel Dieppe. 2nd Edition.

Mosby

3. Illustrated Manual of Orthopaedic Medicine. JH Cyriax, PJ

Cyriax. Butterworths

4. Apley’s System of Orthopaedics and fractures. 8th Edition.

Arnold Publishers.

5. Principles of assessment from a clinical perspective. Landewe

RBM, Van der Heijde DMFM. Best Practice and research Clinical

Rheumatology. Vol no 3 365-379, 2003

6. Neck Pain. Ferrari R, Russell AS: Best Practice and research

Clinical Rheumatology.Vol 17 no 1 57-70.

7. Shoulder Pain. Brox JI. Best Practice and research Clinical

Rheumatology Vol 17 no 1 33-56, 2003.

8. Clinical Examination as a tool for identifying the origin of

musculoskeletal pain. Fouquet B. Best Practice and research

Clinical Rheumatology. Vol 17 no 1 1-15 2003.

9. Assessment of disease activity. Guillemin F. Best Practice

and research Clinical Rheumatology. Vol 17 no 3 415-426.

10. History and the physical examination. Woolf AD. Best

Practice and research Clinical Rheumatology. Vol 17 no 3 381-402

2003.

The History

Distribution of Fibromyalgia

Rubens 3 Graces

Distribution of Osteoarthritis

Distribution of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Distribution of Spondyloarthropathy

Distribution of Gout

Assessment of function

The capsular pattern and normal range of movement

Range of movement of the joints

| Joint | Primary movement | Secondary movement | Tertiary movement |

| Wrist | Flexion and Extension equally | ||

| Elbow | Flexion | Extension | Rotations |

| Shoulder | Abduction | External rotation | Internal rotation |

| Neck | All movements equally except flexion | ||

| Thoracic spine | Extension | Lateral flexion and rotation | |

| Lumbar spine | Lateral flexion | Flexion | Extension |

| Hips | Flexion and Internal Rotation equally | Abduction | |

| Knee | Flexion | Extension | |

| Ankle | Plantar flexion | Dorsiflexion | |

| Subtalar | Varus | Valgus |

Examination of the hand

Examination of the thumb

Examination of the Wrist

Examination of the Elbow

Examination of the shoulder

Examination of the rotator cuff at the shoulder

The acromio clavicular (AC) joint examination

Examination of the neck

Thoracic spine / costovertebral examination

Schober test of lumbar flexion

Examination of the hip joint

Examination of the trochanteric bursa

Examination of the knee

The ankle examination

The subtalar examination

Tarsus and midfoot examination

Plantar fascia and achilles heel examination

Metatarsal examination

Dr D Gotlieb.

drdoc on-line

MBChB FCP(SA)

Cape Town

February 2023

Copyright strictly protected

This article cannot be reproduced under any circumstances

| Go to the waiting room | |

|

|

|